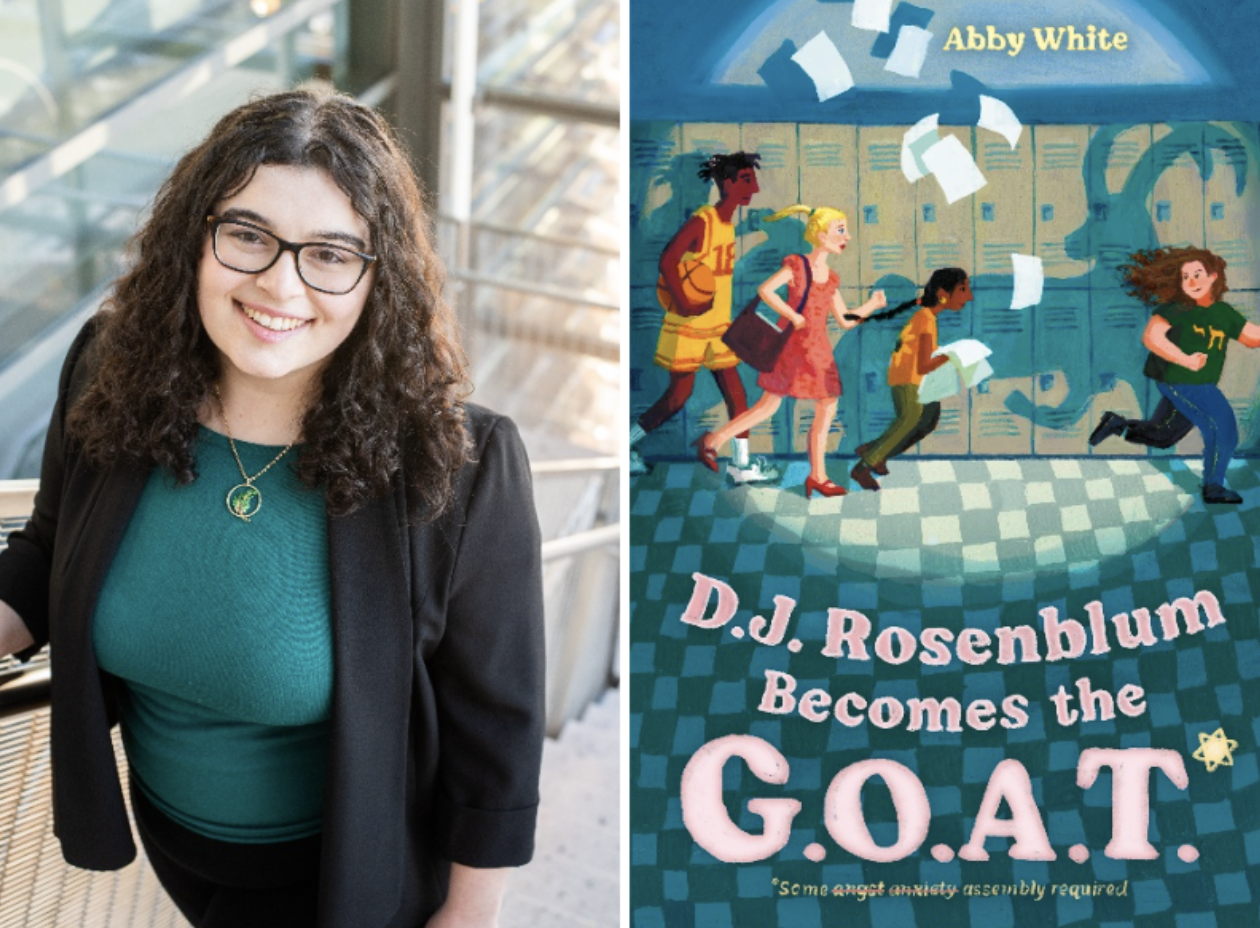

SNR Interviews: Abby White on her debut novel D.J. Rosenblum Becomes the G.O.A.T

In Abby White’s debut novel, D.J. Rosenblum Becomes the G.O.A.T., fourteen-year-old D.J. moves to Briar, Ohio, and begins middle school five years after the death of her beloved cousin, Rachel. Facing a new school, complicated family dynamics, and daunting preparation for her upcoming bat mitzvah, D.J. joins the school newspaper and undertakes her biggest challenge of all: with the help of a new group of misfit friends, she launches a covert investigation to solve the mystery behind Rachel’s suspicious death.

White, who grew up in Ohio, studied creative writing and American studies at Columbia University before earning her MFA from the University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe. She also built an influential career in Washington, D.C. before turning her focus fully to fiction. A fast-paced caper which deftly balances themes of belonging, loss, and resilience, White’s D.J. Rosenblum Becomes the G.O.A.T. explores the messiness of adolescence as D.J. confronts some of life’s hardest truths.

In a wide-ranging conversation, I spoke with White in-depth about her debut novel, why she believes young adult literature carries both cultural weight and responsibility, and advice she has for yet-to-be-published writers.

Beau Noeske: Some universal experiences are represented in this novel: going to middle school and moving to a new community and making new friends. You’re a proud Midwesterner, and you like to talk about “home” with this book. You have a degree from Columbia University, an MFA from UNR, and you had a career in Washington D.C. Yet, this story takes place in a fictionalized version of Shaker Heights where you grew up in Ohio. Why did you want to set this particular story in the Midwest?

Abby White: In some ways, the thing that made me feel most Midwestern was leaving the Midwest. I had a happy upbringing in Ohio. I lately realized how the landscape shaped me when she went to New York for college and D.C. for a job. In early conversations in college with people who’d grown up affluent or on the coasts, I would get asked if she was surrounded by corn and crops. There are a lot of misconceptions about Midwest, and it’s ridiculous to generalize.

There’s an incredible range of landscapes and cultures in so many ways. The publishing industry is very centered on the coasts; NY, San Francisco, some in D.C. for nonfiction. It always felt to me that there were enough people who could write about these places, and I wanted to write about a place that was misunderstood. I wanted to bring something to the table that others couldn’t, and to represent my home without the stereotype of being sandwiched by cornfields. I love a corn maze, let’s be clear! That element of this story – it’s a truism to write what you know, and with this book, D.J. started so similar to myself. I actually consider Briar like a combination of Shaker Heights and Oberlin, a college town. I wanted to combine culture, architecture, and the day-to-day feeling so that it feels a little more isolated and a little more intimate. In a way, I wanted the town to give D.J. a hug. I’m somewhat of a coastal person today, but my home and my people are Midwest, and that’s what felt right for D.J.

BN: Early on at her new school in Briar, there’s an exchange between D.J. and Char where D.J. asks “Make a mess from what?” Char replies: “Life? Snapple? Mess is mess.” And this idea of life being messy is echoed near the end of the book. How did you arrive at that as one of the central ideas in your debut novel?

AW: It’s something I feel about life and it infused itself into the narrative. Growing up, I had an extremely straightforward life—nuclear family, dad was employed, and I lived mostly in one place. And yet, it was still so messy. You just had people making weird decisions that only made sense to them. There was the randomness of things we can’t choose. That was something I learned relatively young that I don’t even think about consciously, it’s just messy to be a human. What this book is about more than anything else is the loss of her cousin by suicide. When I was grappling with the incident which was the loss by suicide of a close friend of mine, I tried to make it make sense. The only turning point when I was able to recover was admitting to myself that there was no reason. It just happens. As a society, we like to talk about everything has cause and effect. We teach kids that you work hard, you’ll be rewarded. And life is messier than that. It’s a cardinal part of my outlook. There were specifics aspects of mess in this story that were crucial to the plot and journey D.J.’s going through.

BN: This book has a lot of wry humor. “We see band geeks in a love pentagon (the trombones…don’t ask)”. Humor is something that’s often hard for writers to engineer, though some people, like yourself, just have a great sense of humor. How were you able to bring that to the page?

AW: I worked really hard at it. It’s been one of my insecurities of writing is I didn’t think I was funny. I wasn’t writing humor the right way. In a previous job, we’d script soundbites. But I’m not a jokey writer. It doesn’t come naturally. I enjoy my own inner monologue and find it humorous. I knew that for D.J.’s book, it would only work if it was funny. The core of this book is an incredibly dark thing that D.J. and the reader are going through, and that can take over the book if not balanced with tone and humor. That’s part of why I employed the mystery genre to make for a fun caper. It’s part of why I explicitly concentrated on making the book funny and making D.J. funny, because it’s not otherwise a funny story. What was successful was asking going interior and asking, what kind of humor do I find myself writing or thinking? The way that D.J. has snide remarks in her head about certain things is very similar to how I think. What made it successful was giving her things to react to. Almost all the humor comes from D.J. herself and giving her weird, idiosyncratic things to comment on. And as I wrote the other characters, I’d give them weird, idiosyncratic things to say. Tory Taylor says you guys need a Lexapro. I really tried to move it to an inverted pyramid structure – if I start at the center with D.J. is funny, that means she needs to react to things, and that means I need to create those things she reacts to.

BN: A lot of the bat mitzvah and d’var Torah preparation scenes were funny, and there’s lot of humor around Judaism in this book. What was your intent behind that?

AW: The Jewish humor was easiest because all Jews are funny and all Jews make fun of ourselves. For the last century and a half, that’s what American Judaism has been – neurosis and making fun of ourselves. But it’s rooted in tradition.

BN: It seems D.J. uses humor to deflect pain?

AW: That’s part of the larger project of what she’s doing from this story. She’s shielding herself from this terrible thing that happened is and feels. This is a girl who is an unreliable narrator who has developed a conspiracy theory as a coping strategy.

BN: Which character or characters surprised you the most as you were writing?

AW: I think Tory. I wasn’t sure initially what role Tory Taylor would play beyond being an antagonist. I knew I wanted her to be more than that, and she became one of my favorite characters in the whole book. She’s so self-possessed in a way that’s hard for anyone to be, let alone teenage girls, and oh, the things I could’ve learned from Tory. She is the most different person from how I was at her age. I loved writing her character and she came alive on the page. Other characters, I really knew their arcs going in. I had been thinking about the story for a year and a half before I wrote it down, so I had their stories in mind.

BN: D.J. Rosenblum Becomes The G.O.A.T is YA—that was your focus in your MFA—but this book explores some adult themes which are timeless: death, mental illness, grieving, blame, religion, and belonging in modern America. Did you start out wanting to address all of these themes, or did they develop organically as you were writing?

AW: I started out not just wanting to address those themes but feeling that those themes were what made the book worthwhile. There certainly are middle-grade books that are light and fluffy, but that’s not what I was attracted to. Books that really shaped me as a young person were by Lois Lowry, John Green, books we think of as adult themes but affect kids just as much. 13- and 14-year-olds see war crimes on TikTok. It’s striking how we wishfully infantilize young people today. Even before social media, life was messy and we went through hard things. One of my formative experiences as a young person was my uncle passed away when I was seven, and my dad, his younger brother, did not take it well and didn’t know how to deal with his grief. Living it but not reading about it as a young person is where gulf becomes frustrating. If not for those themes, there wouldn’t have been a book. There’s no light way to write about a girl who is investigating her cousin’s suicide, but it’s still a story worth writing.

BN: What is the role of YA literature in America today? Did you see yourself undertaking some responsibility with D.J. Rosenblum, or was this just a story that came naturally to you?

AW: Literature for young people – picture book, middle-grade, young-adult, whatever – it’s among the most formative of any society. It’s so often that literature for young people becomes a pop culture phenomenon, much more so that stuff we read a year ago as adults. Look at the censorship and book bans we’re seeing now. People would not be trying to ban these unless they recognize that stories for children have a huge role in who children become and what they value. You never want to be didactic, but there is some message or takeaway and it’s educational. There’s more of a sense of fealty to the reader – you want readers to be themselves and live their best lives. The political moment we’re in, and the gigantic rise in censorship is an affirmation of the fact that literature for young people plays a gigantic role. It’s very clear that these stories are important.

BN: You’ve noted that one of your goals is to uplift marginalized writers and readers. D.J. Rosenblum features many such characters—D.J. herself and her gang of misfit investigators of Char, Tory, and Matt, all of whom could fall under this broad umbrella. What dimensions did that bring to the story?

AW: The diversity of D.J. and her friends were important in a few ways. First of all, stories where everyone has a similar background are mostly boring. One thing I’ve found as a writer is that you really need to stay engaged in the project for the long term, and one of the easiest ways to do it is to make characters very different from each other in background, personality, and community. I think that some people have an anti-woke gut reaction saying this person’s just trying to be progressive. From a craft perspective, this is one way to write something interesting and textured and do the work to write them faithfully and accurately. I’m very grateful to my sensitivity readers who helped me with this book. Morally, I wanted to write a book where almost any kid could see themselves. Literature for young people carries something of an educational aspect.

If you’re writing well with universal themes and feelings, anyone should be able to see themselves in that. Another aspect that’s also a very diverse is the Jewish community. Rabbi Lewis is Latina, Eva is African American, Jonah is Chinese. I want to write something long-lasting, and the Jewish community is much more diverse than is currently represented. Jewish children are becoming more and more diverse, and it’s a fantastic thing. I intentionally wanted to write a book that would continue to resonate. I was actually really rewarded when during my road trip, I met a Japanese woman married to a Jewish man, and I learned about their experiences and felt honored that I could say there was an Asian Jewish character in my book.

BN: This could be a very heavy book with its tragic death of D.J.’s cousin Rachel, and grief can be one of the hardest things to write in a way that holds a reader’s attention. Yet, with the murder mystery structure, this story is fast, this story is fun. Walk us through that authorial decision?

AW: I always knew it was a murder mystery because it was a coping mechanism. I always knew this was a story of a girl that couldn’t accept the truth of what happened. It also speaks to how writers can use intentional craft to pursue broader thematic takeaways. It was fundamentally a craft choice to structure it that way and invert the murder mystery. I always knew the midpoint would be the reveal that it’s actually not a murder mystery, it’s an unreliable narrator who refuses to accept the truth. When you have a clear sense of where you want to go with the story, you can survey the broad toolkit of craft choice.

BN: D.J. is a fascinating character for different reasons, but one is that she’s willing to do some bad things for what she sees as the greater good. And once she crosses one line, she finds it easier and easier to justify an increasingly flexible sense of ethics. But what’s brilliant here is that you really ratchet up the tension, internally, when contrasting this slippery moral code of D.J.’s with her religion, Judaism, which is much more black and white when it comes to ethics. This keeps the pressure on D.J. throughout the story, and the readers are watching this through our fingers. For aspiring authors reading this, how do you continue to ratchet up the tension?

AW: A major element is the tension between a girl with flexible morals in pursuit of the greater good vs. this is also a girl who is faithfully Jewish, including atoning for the sins she commits over the course of the story. To ratchet up the tension, tension by definition, is always between two things. It’s like a rubber band between two ends. You have to create those ends. The ends that have most potential for tension with each other, they have to be very different and very richly and fully written. For D.J., I don’t think as much tension would’ve come across if she wasn’t feeling so internally fraught and the Judaism wouldn’t be a strong counterpoint if it wasn’t spelled out as deeply as it is. You need two juxtaposing forces, but they each need to be full and rich enough so it’s not just an initial juxtaposition, but something such that as each force evolves, the tension naturally ratchets up. It doesn’t need to come in the initial draft, but then it needs to come up in editing.

BN: What books and authors have been your biggest influences, both for you personally and for D.J. Rosenblum Becomes the G.O.A.T.?

AW: I’ve read so much and so widely that to some extent my biggest influence is the variety of stuff I’ve read and how different books in the same genre could be. J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter was gigantic for me. My first real forays were Harry Potter fanfiction. Those are books that have a strong theme and are educational without being didactic. They communicate something higher than and more than an interesting story and good characters. Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson series is educational without being didactic and he builds his points beautifully over the course of the story. It speaks to a real knowledge of voice and audience and how to write things for a specific audience. I was lucky enough to meet him at an event, he’s a straight and cis white guy, and his earlier works were more homogenous. He has intentionally made his books more diverse, and one of his books was one of the first I read which had a trans character. It speaks to the evolution he’s had as an author, and he’s a good example of thinking what kind of author I want to be. He's clearly an author who wanted to write books where kids could see themselves in them. You don’t need to be defensive about it, but you can change and do things better.

There’s something of the humorous voice of Percy Jackson that influenced the voice of D.J. Jonathan Stroud is an author I love. I’m very much of the John Green generation with The Fault in Our Stars. He had a tectonic influence on genre the way that Judy Bloom had previously. It’s about taking what’s looked at as light material and instead telling universal truths. I’m conscious that D.J. Rosenblum is a John Green book. Traci Chee is another author I admire. Her writing is just great and how she thinks about writing is really inspiring to me.

BN: A lot of SNR’s readers are writers. They probably work jobs that they’re looking to escape, and they dream of writing that novel which will pull them out of the nine-to-five grind. What is something you believe separates talented writers from published writers?

AW: A lot of writers I talk to want to be told the right way to do something. They might say,

“What is THE way to create this feeling or have this effect or get published?” I think that looking for the right way to do anything in writing is the wrong question. There’s no single right way. It’s a question of do you as a writer know your voice and your writing well enough to get through this plot hole or this character hiccup or whatever the issue might be. The real difference between talented and published is luck. I know a lot of great writers who haven’t gotten published yet. Difference is not asking about THE right way to do things anymore, but rather, seeing their story holistically so they can ask better and more specific questions based on their expertise.

BN: Has there been feedback from your readers that surprised you or inspired you?

AW: Some readers have asked if D.J. and Tory are canon? Maybe I’m so geared toward fanfiction that yes, in my mind, they’re obviously going to get together. If anything, I have all sorts of ideas for their adult lives together. This is such a personal story for me in writing a character who in many ways is similar to myself, and writing a set of feelings I was very much enmeshed in as I was writing this, so I’m moved every time a reader says this is special and I needed to read this set of feelings. Something that felt most successful to me is when someone said it’s the first book they read about suicide loss they’d read that really captured the anger.

BN: What question do you wish people asked you to better understand the heart of this story?

AW: “Why did I make this YA instead of middle grade?” Thirteen and fourteen year olds are teenagers, and being a teenager is very different from being in upper elementary school or being 12, even. Generally middle grade is 8-12, and YA is 12-18, and there’s so much focus on the 16-18 range, and the 12-16 range gets short shrift. That is the most volatile age in anyone’s life, certainly mine. My brain wasn’t in the same place as my body and I didn’t know what to do, so from a mission driven standpoint I wanted to write for those readers. The Bat Mitzvah construct meant D.J. was going to be 12 or 14, and I always felt strongly that 13 or 14 is young adult. A World Worth Saving is a great example of a middle grade book, but so many aren’t age appropriate for the experiences and feelings that age group is really feeling. It just felt truer. This is where publishing industry conventions come into play. There shouldn’t be cursing in middle grade book, but when I was fourteen, I never cursed more than when I was that age and had something to prove.

BN: From when you started this book until you finished, what is something you as an author, or even as a person, got better at while writing D.J. Rosenblum?

AW: Everything. But mainly it was intentionality in craft. There were a lot of craft decisions I was making writing this book. I wasn’t thinking of my decisions in terms of craft, but the more I wrote and studied and learned at UNR for my MFA, the more I started thinking about these choices in terms of craft which made them repeatable rather than just on instinct. I learned to see instinctive moves as craft choices and thereby being able to hone my skills in those areas and replicate them in future work.

BN: Where can we find you and your book?

AW: I'm @abbywhitewrites on Instagram, Twitter, and Bluesky. (Technically TikTok, too, but I've never used it.) My website is abbywhitewrites.com and my Substack is "After Dear Abby": https://abbywhitewrites.substack.com/.

Shop local this holiday season and support your independent bookstore by purchasing D.J. Rosenblum Becomes the G.O.A.T. in person or through bookshop.org!

“There certainly are middle-grade books that are light and fluffy, but that’s not what I was attracted to. Books that really shaped me as a young person were by Lois Lowry, John Green, books we think of as adult themes but affect kids just as much. 13-and 14-year-olds see war crimes on TikTok. It’s striking how we wishfully infantilize young people today.”